Blog post 6: Don't forget about aquifers

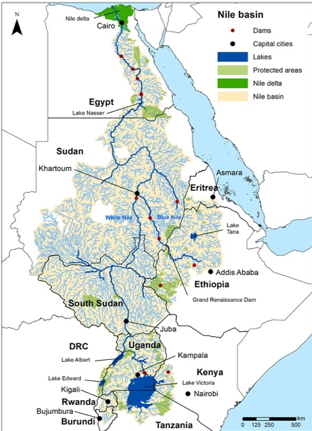

To enhance last week’s post on transboundary water resources, this entry will briefly discuss shared sub-surface resources. The video below introduces groundwater in Africa and highlights the associated opportunities and challenges: Groundwater accounts for >80% of sub-Saharan Africa’s domestic rural water supply ( Calow et al. 2010 ). Yet, people are not always aware of its transboundary nature (fig.1) as, unlike rivers, aquifers cannot be seen. Thus, groundwater consumers may also be unaware of who else uses the aquifer or the impacts their use/contamination has elsewhere. So, whilst there is less explicit conflict over groundwater ( Kulkarni and Aslekar 2018 ), there is perhaps more potential for political disputes. Moreover, with climate change leading to higher evaporative losses of surface waters ( Serdeczny et al. 2017 ) but increasing groundwater recharge due to fewer but heavier rainfall events ( Owor et al. 2009 ), groundwater is likely to become an increasingly relie