Blog post 5: Dam discussions in deadlock

The construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa’s largest dam, has been fraught with problems including corruption scandals (Ljubas 2019), death of the chief engineer (Champion and Manek 2019) and military threats (Walsh and Sengupta 2020). Additionally, it was recently reported that GERD negotiations have reached another stalemate, after Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan failed to agree on a procedure to complete talks (Abdallatif 2020).

The Nile

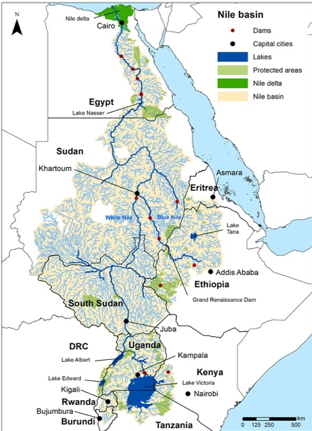

The Nile basin covers 3.3million km2, spanning 11 countries (fig. 1). The two main tributaries of the Nile River are the White Nile (source in Burundi) and the Blue Nile (source in Ethiopia). The latter provides 85% of the water flowing into the Nile (NBI 2020) and is the tributary upon which GERD is situated. Conflict over transboundary water resources can occur for a number of reasons including disputes over water quality and contamination, navigation and environmental protection (Matthews and St.Germain 2007). However, the primary reason for the ongoing GERD dispute is the allocation of water.

Figure 1. Map of the Nile Basin that includes the capital cities of the riparian countries, tributaries, major lakes, dams and protected areas. Source: Allan et al. 2019

Politics on the Nile has resulted in Egypt disproportionally benefitting and developing over Ethiopia.

-The 1929 (modified in 1959) Nile Water Agreement gave Egypt rights to 87% of the Nile’s water and Sudan the remainder (Barnaby 2009), resulting in power asymmetry (Zeitoum and Warner 2005). Ethiopia has the highest population in the Nile Basin and provides 85% of the river water (NBI 2020) but was not recognised as a controlling power. This combined with colonial British interests in agricultural infrastructure enabled Egypt and Sudan to have the most developed irrigation systems in the region (Kimenyi and Mbaku 2015).

-The 2015 Declaration of Principles (DoP) restored power symmetry (Salman 2016) by recognising equality of all Nile states, but does not compensate for this historical development advantage. Additionally, it is argued the DoP actually reaffirmed previous colonial agreements by recognising Egypt’s claim on GERD management (Bayeh 2016).

Conflict

Whilst there are many pros and cons associated with building dams (table 1), I will highlight a few political aspects I think are key when exploring Ethiopia and Egypt’s viewpoints in the GERD conflict.

Table 1. Summary of the key arguments for and against building a dam. Source: made by author

The project

GERD allows Ethiopia to launch a ‘hydropolitical offense’ (Conniff 2017), harnessing the Nile for their own development and correcting historical injustices. It increases their power over the Nile and, through selling surplus hydropower, extends their economic influence (Conniff 2017).

However, GERD challenges Egypt’s historical hegemonic position and threatens the nation’s identity which revolves around the Nile River (Gebreluel 2014). Additionally, Egypt’s President and former head of the military, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, is highly sensitive to suggestions he overlooks national security (Walsh and Sengupta 2020). Thus, he takes an especially firm stance on this issue, making compromise and cooperation particularly challenging.

Latest stalemate

The timetable to fill the dam is the latest disagreement between Egypt and Ethiopia. Prime Minster Abiy Ahmed Ali is under pressure to deliver returns on GERD since citizens purchased government bonds to help fund the project. Additionally, in a country that thinks of itself as an emerging power, Abiy Ahmed cannot be seen to give in to Egyptian influence. These pressures are magnified in the face of internal political struggles (Pilling and Schipani 2020) and the upcoming national elections (Walsh and Sengupta 2020).

Egypt rely on the Nile for 97% freshwater needs and thus have focused on the short-term impacts rather than recognising the benefits of GERD in the longer term. Filling of the GERD would reduce river flow downstream, affecting Egypt’s hydroelectric power generation and water resources. However, the occurrence of hot, dry years in the basin is expected to increase (Coffel et al. 2019). GERD could combat the subsequent increased variability of the Nile, benefitting all riparian countries, by storing water upstream where, compared to Egypt, evaporation rates are less (Pearce 2015). It would also reduce sedimentation and so increase capacity of dams downstream.

Photograph of Cairo, Egypt, situated on the River Nile. Source: Imster 2019

Comments

Post a Comment