Blog post 3: Show me a drought and I’ll show you a dysfunctional government

Previously I mentioned Watkins argument that inequality and power imbalances are central to water crises (2006). This idea is likely to feature a lot throughout my blog as power is inherent to politics whereby groups of people make decisions (Axford et al. 1997). This post will outline how the physical landscape and climate of Africa contributes to inequality. It aims to contextualise my blog and provide a grounding from which we can explore how this inequality has (or has not) been compounded by politics in future posts.

Photo from meeting of the Executive Committee of the African Ministers’ Council Water (AMCOW) whose mission is to provide ‘political leadership, policy direction and advocacy in the provision, use and management of water resources’. Source

Freshwater availability

The terms ‘water scarcity’ and ‘water stress’ are often used to describe a country or region’s freshwater availability. Whilst there is much debate over their definitions, values of 1700m3/capita/year and 1000m3/capita/year are commonly used boundaries for water stress and water scarcity respectively (Damkjaer and Taylor 2017). As you can see from figure 1, the problems of water availability in Africa are not one of volume but distribution, both in time and space (Ashton 2007). However, due to the simplicity of the metrics used to assess water availability, this map can be misleading. Most assessments are based on the Water Stress Index which does not account for seasonal variability in river discharge nor alternative water resources such as groundwater, reservoirs or rainfall (Damkjaer and Taylor 2017). These alternative sources are extremely important to consider when looking at water supply as they may significantly influence water provision. Groundwater, for example, accounts for over 80% of domestic rural water supplies in sub-Saharan Africa (Calow et al. 2010).

Figure 1. Map of water scarcity in Africa as defined by the water stress index (WSI). Source: Damkjaer and Taylor 2017

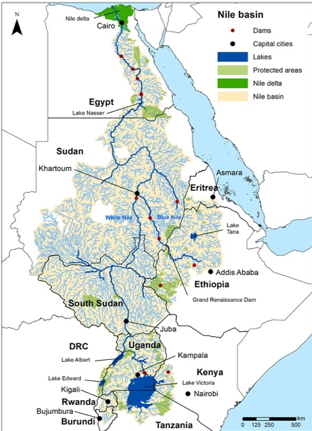

Seasonality is primarily driven by the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). As a result of ITCZ movement, rainfall is often bimodal at the equator but in areas of southern and northern Africa (e.g. 20o S and 20oN) there is only one rainy season centred around January and July respectively. Understandably, this leads to extreme variability in river discharge in these areas of unimodal rainfall. Large areas of Africa experience severe drought in the dry season and subsequent flooding when it rains (Ashton 2002). This problem is likely to get worse in the future as climate change exacerbates the situation (Smakhtin et al. 2001; Urama and Ozor 2010). The greater water insecurity and a reliance on other freshwater reservoirs in the dry season, like aquifers which are often transboundary, heightens political tensions at both local and national scales (Earle 2010). Over-extraction of groundwater lowers the water table which, depending on the hydraulic diffusivity, can have ramifications elsewhere in the area (Aeschbach-Hertig and Gleeson 2012). Additionally, groundwater supplies can take millennia to fully replenish (Simmers 2013) and therefore present-day decisions about groundwater extraction also affect water supplies well into the future.

Safe water

Now it is important to remember that water accessibility does not necessarily mean access to safe water. Water resources can be contaminated or polluted through faeces, industrial activities and dumping, for example. North Africa is the most water stressed region in Africa (fig. 1) yet 93% people have access to safe water (WHO and UNICEF 2015). Conversely, only 68% people in sub-Saharan Africa do. As I hope to demonstrate in future blog posts, access to safe water is predominantly influenced by water management and infrastructure (e.g. piped water networks) and therefore economics and politics. Who decides what water resources to use? Who decides what infrastructure is built and where? Who decides who gets access to safe water?

Comments

Post a Comment