Blog post 8: Dodgy dealings - water grabbing in Sierra Leone

Last month the Sierra Leone Land Alliance (SSLA) released a report titled ‘Land grabbing in a time of Covid-19 in Sierra Leone’ in which they said land ownership was a primary cause of tension between the government and citizens (Politico 2020). This notion is not new: land tension and unequal distribution of resources has frequently been stated as a major driver of the Sierra Leone civil war (Sturgess and Flower 2013).

This post will explore land grabbing in Sierra Leone in more detail, highlighting why it’s such a contentious issue. It will illuminate the reasons behind the government’s decision to lease/sell land and why citizens are so opposed to it. Unlike my other blog entries, it will focus on foreign players’ involvement in African hydropolitics and how they are partly to blame for the poor relationship between Sierra Leone citizens and government.

Land grabbing

First a quick introduction to land grabbing: what is it and how does it relate to water and development in Africa? Land grabbing or transnational land acquisitions refer to the transfer of landuse and/or ownership rights from local communities to foreign investors through large-scale land acquisitions (Rulli et al. 2013). It is contentious because it is often done without prior consent of the landusers and/or owners. Water is a major driver of LSLAs (Franco et al. 2013) as it is needed to sustain agricultural production: 83% of freshwater use in Africa is for agriculture (Wada et al. 2011). Thus, every land grab is also a water grab.

Sierra Leone

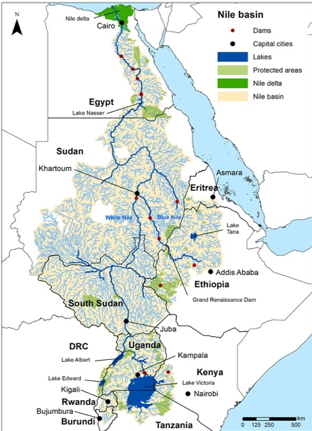

Following the civil war, Sierra Leone, backed by the World Bank, has pushed to attract large-scale agribusiness investments to aid economic recovery (Tran 2013). Despite, the multiple land grabs in Sierra Leone since 2000 (fig. 1), the 2011 acquisition of 6,500ha of farmland in the Pujehun region in particular, has garnered a lot of media attention (Tran 2013; Gbandia 2016). The Sierra Leone government leased the land to Luxembourg-based Socfin Group for 50 years. In addition to paying annual rents, Socfin promised jobs and the construction of roads, schools and a hospital, benefiting the local communities (Mousseau et al. 2012). However, subsequent broken promises and opposition from local communities have since contributed to the tension between the government and citizens.Figure 1. Land deals concluded in Sierra Leone (excluding mining) between 2000 and 2016. Overall, 24 investors from 16 different countries engaged in LSLAs. Socfin land grabs are highlighted in red. Source

Who should be held accountable?

The government?

The primary justification for promoting LSLA is based on the claim that 85-89% of the country’s arable land is ‘unused’ (Sturgess and Flower 2013). However, a report by GIZ concluded that there was in fact no vast ‘unused’ arable land (2011) as fallow land was required by farmers. This misunderstanding or purposeful oversight of existing farming practices not only displaced communities but also impacted their economic and social livelihoods. Protestors opposing the land grab were arrested and some detained without food for 8 days. Other grievances against the government included a lack of consultation with local land users, poor transparency and communication, and bribery of the Paramount Chief who held the most power amongst the traditional communities (Mousseau et al. 2012).Socfin?

In the construction of the plantation, crucial forests and agricultural land was lost with little compensation to local farmers. In fact, there appears to be minimal consideration of local communities much beyond their use as an exploitable resource. Working conditions are described as “near-slavery” with low wages, long hours, insufficient toilets and a days’ forfeited pay if you are 10+ minutes late after lunch (Mousseau et al. 2012). Remember all land grabs are water grabs? Well, Socfin are likely extracting water for palm oil processing from underlying shallow basement aquifers or the Moa river (fig. 2) (UNICEF 2012). Whilst previously, a synergy between the distributed small holder agriculturalists and distributed low intensity use of groundwater existed (Schumacher 1973), Scofins more intense water demands may deplete low yielding basement aquifers. Not only does this extraction affect local communities’ water supply, but it may impact others who use the same aquifer or are downstream, leading to more widespread discontent.Figure 2. Map of the potential water sources (excluding rainfall collection) for Socfin extraction. They have unrestricted water use and access, only paying $0.0007/m3 extracted (Mousseau et al. 2012). Volumes extracted are unregulated and therefore actual water sources used are unknown. Source: map made by author (me) using data from Berkeley, WorldBank, HumData and BGS.

Comments

Post a Comment