Blog post 10: Reflections

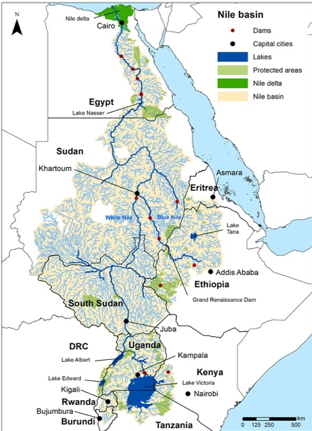

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed exploring the political side of water and development over these last 9 weeks and have learnt a lot in the process. In this blog, I’ve tried to cover different regions of Africa (figure 1) so as not to confine myself to certain cultures, societies, political institutions and economies. The blog has largely followed the structure outlined in my introductory post, discussing how politics is intertwined with water management and provision at individual to international scales. Previously, I primarily associated politics with formal institutions and legal frameworks, but this blog has really highlighted the omnipresent nature of politics to me. Figure 1. Map highlighting countries I’ve covered in this blog. Source At the beginning of the blog I set out how physical characteristics affect safe water access. Whilst I still believe the physical environment plays a part in water distribution and access, it’s become clear that politics is at the centre of water iss...