Blog post 1: Introductions

Hello and welcome to my blog where I discuss hydropolitics in Africa!

This blog post is a quick introduction to me and why I'm passionate about African hydropolitics. It will also give a brief insight into why water is such an important political issue and touch upon some topics I hope to explore more in future posts.

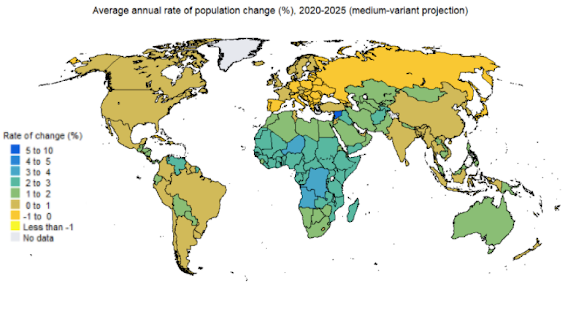

I grew up in the cultural melting pot that is Johannesburg, South Africa, and this sparked my interested in the Africa continent. Although whilst living there I experienced hosepipe bans and occasional water shortages due to poorly maintained water pipes, it was not until I moved to the U.K. that the topic of hydropolitics in Africa really grabbed my attention. When back visiting Johannesburg, I volunteered at the Yeoville Community School which caters to children with challenging socioeconomic backgrounds. Most of the children I met lived in informal housing in the surrounding townships, such as Alexandra, Vooslorus and Orange Farm and almost all of them looked forward to attending school every day. Common reasons for this included the school having clean toilets, greater access to cleaner water and being viewed as a safe place to play. A Human Development report (Watkins 2006) suggests that problems with water and sanitation services are largely restricted by class and thus common in informal settlements around the world. In sub-Saharan Africa particularly, the high population growth (fig.1) combined with the fastest urbanisation rate in the world (Saghir and Santoro 2018) is likely to result in the expansion of informal settlements and increased pressures on water provision.

Figure 1. Map depicting population change 2020-2025. Source: UN 2019

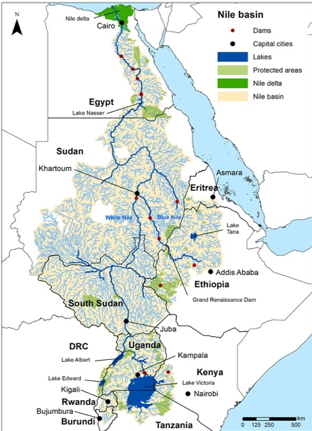

Water is not just a life source; it is required for almost all production and thus water security is seen as essential for economic growth and development (Grey and Sadoff 2007). Subsequently, water is a highly politicised resource and has, unsurprisingly, been at the heart of conflicts involving different African countries in the past. For example, the ongoing transboundary disputes over water in the Nile Basin between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan (Kimenyi and Mbaku 2015): a case study I will explore in more detail in a subsequent post. Although the right to water has been recognised as a fundamental human right (UN 2010), issues, rooted in politics, still remain and influence water provision in areas and thus a citizens ability to claim this right. Watkins (2006) argues that water crises are due to inequality and power imbalances between those that are affected by problems and those with the power to fix them. In order to explore this idea further, a basic understanding of how the physical landscape of Africa contributes to this inequality is needed.

Recent negotiations over the timetable for filling the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in the Nile Basin has increased tensions between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt. Image source: Daily News Egypt

Therefore, the next post will contextualise this blog by looking at how the physical landscape of Africa affects some people’s access to water and leads to water scarcity in some countries. Then, the blog will highlight how politics is intertwined with water management and provision by exploring a series of case studies: these will look at both national and local politics surrounding water resources and related infrastructures across different African countries. I specifically plan to dive further into the aforementioned transboundary water issues; Watkins’ power imbalance argument (2006) in the context of the Cape Town water crisis; and local hydropolitics and sanitation.

Very easy to read and well written! I really like how you have drawn on your own experience to set up the scope and focus of your first post (and blog as a whole). Great synthesis of peer reviewed material and referencing using hyperlinks.

ReplyDelete(GEOG0036 PGTA)